Contracts & schemas

In Kore, each subject is associated to a schema that determines, fundamentally, its properties. The value of these properties may change over time through the emission of events, being necessary, consequently, to establish the mechanism through which these events perform such action. In practice, this is managed through a series of rules that constitute what we call a contract.

Consequently, we can say that a schema always has an associated contract that regulates how it evolves. The specification of both is done in governance.

Inputs and outputs

Contracts, although specified in the governance, are only executed by those nodes that have evaluation capabilities and have been defined as such in the governance rules. It is important to note that Kore allows a node to act as evaluator of a subject even if it does not possess the subject’s events chain, i.e., even if it is not witness. This helps to reduce the load on these nodes and contributes to the overall network performance.

To achieve the correct execution of a contract, it receives three inputs: the current state of the subject, the event to be processed and a flag indicating whether or not the event request has been issued by the owner of the subject. Once these inputs are received, the contract must use them to generate a new valid state. Note that the logic of the latter lies entirely with the contract programmer. The contract programmer also determines which events are valid, i.e. decides the family of events to be used. Thus, the contract will only accept events from this family, rejecting all others, and which the programmer can adapt, in terms of structure and data, to the needs of his use case. As an example, suppose a subject representing an user’s profile with his contact information as well as his identity; an event of the family could be one that only updates the user’s telephone number. On the other hand, the flag can be used to restrict certain operations to only the owner of the subject, since the execution of the contract is performed both by the events it generates on its own and by external invocations.

When a contract is finished executing, it generates three outputs:

-

Success flag: By means of a Boolean, it indicates whether the execution of the contract has been successful, in other words, whether the event should cause a change of state of the subject. This flag will be set to false whenever an error occurs in obtaining the input data of the contract or if the logic of the contract so dictates. In other words, it can and should be explicitly stated whether or not the execution can be considered successful. This is important because these decisions depend entirely on the use case, from which Kore is abstracted in its entirety. Thus, for example, the programmer could determine that if, after the execution of an event, the value of one of the subject properties has exceeded a threshold, the event cannot be considered valid.

-

Final state: If the event has been successfully processed and the execution of the contract has been marked as successful, then it returns the new state generated, which in practice could be the same as the previous one. This state will be validated against the schema defined in the governance to ensure the integrity of the information. If the validation is not successful, the success flag is cancelled.

-

Approval flag: The contract must decide whether or not an event should be approved. Again, this will depend entirely on the use case, being the responsibility of the programmer to establish when it is necessary. Thus, approval is set as an optional but also conditional phase.

CAUTION

Kore contracts work without any associated status. All the information they can work with is what they receive as input. This means that the value of variables is not retained between executions, marking an important difference with respect to contracts on other platforms, such as Ethereum.Life cycle

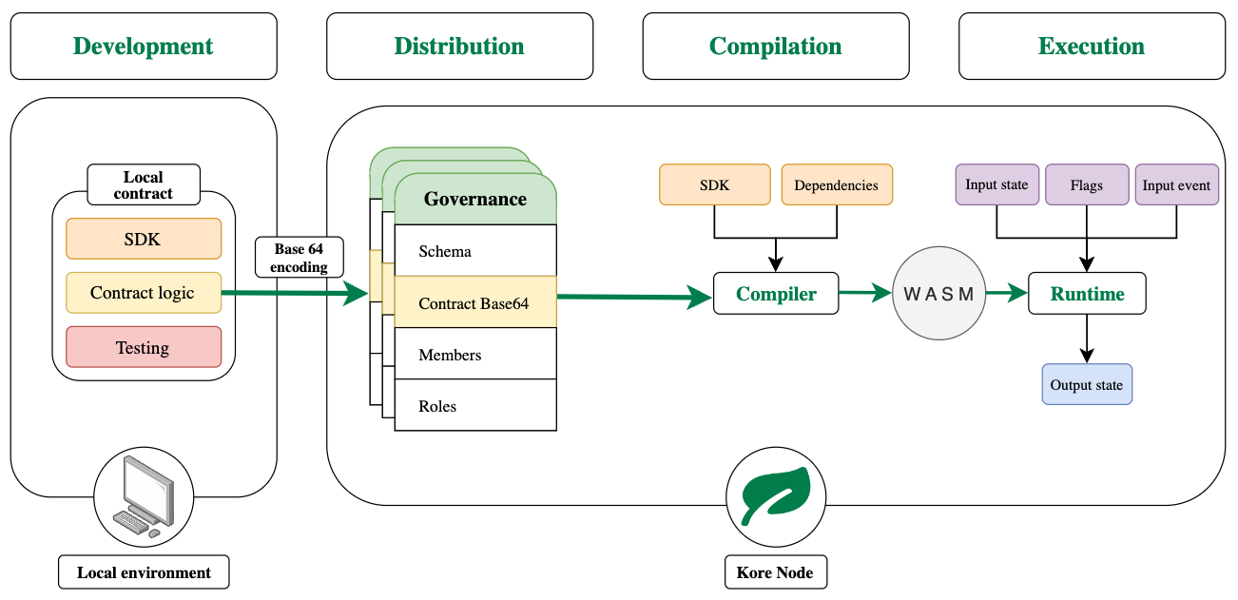

Development

Contracts are defined in local Rust projects, the only language allowed for writing them. These projects, which we must define as libraries, must import the SDK of the contracts available in the official repositories and, in addition, must follow the indications specified in “how to write a contract”.

Distribution

Once the contract has been defined, it must be included in a governance and associated to a schema so that it can be used by the nodes of a network. To this end, it is necessary to perform a governance update operation in which the contract is included in the corresponding section and coded in base64. If a test battery has been defined, it does not need to be included in the encoding process.

CAUTION

Since the Kore nodes are in charge of contract compilation, it is necessary that the base64 includes the contract in its entirety. In other words, the contract should be written entirely in a single file and encoded.

This is a current limitation and other alternatives are expected to be available in the future.

Compilation

If the update request is successful, the governance status will change and the evaluator nodes will compile the contract as a Web Assembly module, serialize it and store it in their database. This is an automated and self-managed process, so no user intervention is required at any stage of the process.

After this step, the contract can be used.

Execution

The execution of the contract will be done in a Web Assembly Runtime, isolating its execution from the rest of the system. This avoids the misuse of its resources, adding a layer of security.

Rust and WASM

Web Assembly is used for contract execution due to its characteristics:

- High performance and efficiency.

- It offers an isolated and secure execution environment.

- It has an active community.

- Allows compilation from several languages, many of them with a considerable user base.

- The modules resulting from the compilation, once optimized, are lightweight.

Rust was chosen as the language for writing Kore contracts because of its ability to compile to Web Assembly as well as its capabilities and specifications, the same reason that motivated its choice for the development of Kore. Specifically, Rust is a language focused on writing secure, high-performance code, both of which contribute to the quality of the resulting Web Assembly module. In addition, the language natively has the resources to create tests, which favors the testing of contracts.